The History of Synthetic Testosterone

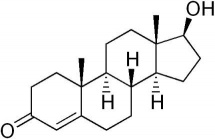

The testosterone chemical structure

The testosterone chemical structure

The History of Synthetic Testosterone

Testosterone has long been banned in sports as a performance-enhancing drug. This use may soon be accepted in medicine alongside other legitimate hormonal therapies (by John M. Hoberman and Charles E. Yesalis )

On June 1, 1889, Charles Edouard Brown-Sequard, a prominent French physiologist, announced at the Societe de Biologie in Paris that he had devised a rejuvenating therapy for the body and mind. The 72-year-old professor reported that he had drastically reversed his own decline by injecting himself with a liquid extract derived from the testicles of dogs and guinea pigs. These injections, he told his audience, had increased his physical strength and intellectual energy, relieved his constipation and even lengthened the arc of his urine.

Almost all experts, including some of Brown-Sequard's contemporaries, have agreed that these positive effects were induced by the power of suggestion, despite Brown-Sequard's claims to the contrary. Yet he was correct in proposing that the functions of the testicles might be enhanced or restored by replacing the substances they produce. His achievement was thus to make the idea of the "internal secretion," initially proposed by another well-known French physiologist, Claude Bernard, in 1855, the basis of an organotherapeutic "replacement" technique. Brown-Sequard's insight that internal secretions could act as physiological regulators (named hormones in 1905) makes him one of the founders of modern endocrinology. So began an era of increasingly sophisticated hormonal treatments that led to the synthesis in 1935 of testosterone, the primary male hormone produced by the testicles.

Since then, testosterone and its primary derivatives, the anabolic-androgenic

steroids, have led a curious double life. Since the 1940s countless elite

athletes and bodybuilders have taken these drugs to increase muscle mass and to

intensify training regimens. For the past 25 years, this practice has been

officially proscribed yet maintained by a $1-billion international black market.

That testosterone products have served many therapeutic roles in legitimate

clinical medicine for an even longer period is less well known. Fifty years ago,

in fact, it appeared as though testosterone might become a common therapy for

aging males, but for various reasons it did not gain this "legitimate"

mass-market status. Perhaps most important, physicians were concerned that these

drugs often caused virilizing side effects when administered to women, including

a huskier voice and hirsutism.

Today, however, there is compelling evidence that these spheres of "legitimate"

and "illegitimate" testosterone use are fusing. Further research into the risks

and the medical value of anabolic-androgenic steroids is under way. Indeed,

scientists are now investigating the severity of such reported temporary

short-term side effects as increased aggression, impaired liver function and

reproductive problems. And some physicians are currently administering

testosterone treatments to growing numbers of aging men to enhance their

physical strength, libido and sense of well-being. Our purpose here is to

describe the largely forgotten history of male hormone therapy that has

culminated in the prospect of testosterone treatments for millions of people.

Organotherapy

Brown-Sequard provided samples of his liquide testiculaire free of charge to

physicians willing to test them. The offer generated a wave of international

experiments aimed at curing a very broad range of disorders, including

tuberculosis, cancer, diabetes, paralysis, gangrene, anemia, arteriosclerosis,

influenza, Addison's disease, hysteria and migraine. This new science of animal

extracts had its roots in a primitive belief that came to be known as similia

similibus, or treating an organ with itself. Over many centuries since ancient

times, physicians had prescribed the ingestion of human or animal heart tissue

to produce courage, brain matter to cure idiocy and an unappetizing array of

other body parts and secretions--including bile, blood, bone, feces, feathers,

horns, intestine, placenta and teeth--to ameliorate sundry ailments.

Sexual organs and their secretions held a prominent place in this bizarre

therapeutic gallery. The ancient Egyptians accorded medicinal powers to the

testicles, and the Roman scholar Pliny the Elder reports that the oil-soaked

penis of a donkey or the honey-covered penis of a hyena served as sexual

fetishes. The "Ayurveda of Susruta" (circa 1000 B.C.) recommended the ingestion

of testis tissue as a treatment for impotence. Johannes Mesue the Elder (A.D.

777-857) prescribed a kind of testicular extract as an aphrodisiac. The "Pharmacopoea

Wirtenbergica," a compendium of remedies published in 1754 in Germany, mentions

horse testicles and the phalluses of marine animals. These therapeutic exotica

are significant because they dramatize the impossibility, for ancients and

moderns alike, of separating sexual myth from sexual biology.

Two of the researchers inspired by Brown-Sequard's work were the Austrian

physiologist Oskar Zoth and his compatriot Fritz Pregl, a physician who

eventually turned to analytic chemistry and received a Nobel Prize in 1923. When

sports physiology was in its infancy, these men investigated whether testicular

extracts could increase muscle strength and possibly improve athletic

performance. They injected themselves with a liquid extract of bull's testicles

and then measured the strength of their middle fingers. A Mosso ergograph

recorded the "fatigue curve" of each series of exercises.

Zoth's 1896 paper concluded that the "orchitic" extract had improved both

muscular strength and the condition of the "neuromuscular apparatus." Most

scientists now would say these were placebo effects, a possibility these

experimenters considered and rejected. Yet the final sentence of this

paper--"The training of athletes offers an opportunity for further research in

this area and for a practical assessment of our experimental results"--can lay

claim to a certain historical significance as the first proposal to inject

athletes with a hormonal substance.

The growing popularity of male extracts prompted other scientists to search for

their active ingredient. In 1891 the Russian chemist Alexander von Poehl singled

out spermine phosphate crystals, first observed in human semen by the

microscopist Anton van Leeuwenhoek in 1677 and again by European scientists in

the 1860s and 1870s. Poehl claimed correctly that spermine occurs in both male

and female tissues, and he concluded that it increased alkalinity in the

bloodstream, thereby raising the blood's capacity to transport oxygen.

This was an interesting observation insofar as hemoglobin does pick up oxygen in

a slightly alkaline environment and releases it when the pH is slightly acidic.

But he was incorrect in that no chemical mediates the binding of oxygen to

hemoglobin. Still, Poehl believed he had improved on Brown-Sequard's work, for

if spermine did accelerate oxygen transport, then it could claim status as a "dynamogenic"

substance, having unlimited potential to enhance the vitality of the human

organism. As it turned out, spermine's function remained unknown until 1992,

when Ahsan U. Khan of Harvard Medical School and his colleagues proposed that it

helps to protect DNA against the harmful effects of molecular oxygen.

Testicle Transplants

>Between the flowering of spermine theory before World War I and the synthesis of

testosterone two decades later, another sex gland therapy debuted in the medical

literature and made wealthy men of a few practitioners. The transplantation of

animal and human testicular material into patients suffering from damaged or

dysfunctional sex glands appears to have begun in 1912, when two doctors in

Philadelphia transplanted a human testicle into a patient with "apparent

technical success," as a later experimenter reported.

A year later Victor D. Lespinasse of Chicago removed a testicle from an

anesthetized donor, fashioned three transverse slices and inserted them into a

sexually dysfunctional patient who had lost both of his own testicles. Four days

later "the patient had a strong erection accompanied by marked sexual desire. He

insisted on leaving the hospital to satisfy this desire." Two years later the

patient's sexual capacity was still intact, and Lespinasse described the

operation as an "absolutely perfect" clinical intervention.

The most intrepid of these surgeons was Leo L. Stanley, resident physician of

San Quentin prison in California. Stanley presided over a large and stable

population of testicle donors and eager recipients. In 1918 he began

transplanting testicles removed from recently executed prisoners into inmates of

various ages, a number of whom reported the recovery of sexual potency.

In 1920 "the scarcity of human material," Stanley wrote, prompted him to

substitute ram, goat, deer and boar testes, which appeared to work equally well.

He performed hundreds of operations, and favorable word-of-mouth testimony

brought in many patients seeking treatment for an array of disorders: senility,

asthma, epilepsy, diabetes, impotence, tuberculosis, paranoia, gangrene and

more. Having found no ill effects, he concluded that "animal testicular

substance injected into the human body does exert decided effects," including

"relieving pain of obscure origin and promotion of bodily well-being."

Early organotherapy of this kind existed on the boundary separating legitimate

medicine from quackery. Stanley's work, for example, was respectable enough to

appear in the journal "Endocrinology." Like Brown-Sequard, he complained about

the "'lost manhood' charlatans" and "medical buccaneers" who navigated "this

poorly charted sea of research" in a half-blind state and sometimes pursued

financial gain rather than medical progress. Yet Stanley himself performed

operations without hesitation and was persuaded by much ambiguous evidence. And

the controversial "monkey gland" transplants performed by Serge Voronoff during

the 1920s earned this Russian-French surgeon a considerable fortune.

In an appreciative retrospective monograph, the medical historian David Hamilton

argues for Voronoff's sincerity at a time when endocrinology was a new field and

medical ethics committees were few and far between. Although medical journals

sounded regular warnings against "marvel mongering," "haphazard, pluriglandular

dosing" and "extravagant therapeutic excursions," they expressed some cautious

optimism as well. Given the limited knowledge and therapeutic temptations of

this era, these treatments are better described as cutting-edge medicine than as

fraud.

The Isolation of Testosterone

Before Stanley and his fellow surgeons started performing transplant operations,

other scientists had begun searching for a specific substance having androgenic

properties. In 1911 A. Pezard discovered that the comb of a male capon grew in

direct proportion to the amount of animal testicular extracts he injected into

the bird. Over the next two decades researchers used this and similar animal

tests to determine the androgenic effects of various substances isolated from

large quantities of animal testicles or human urine. Their quest entered its

final stage in 1931, when Adolf Butenandt managed to derive 15 milligrams of

androsterone, a nontesticular male hormone, from 15,000 liters of policemen's

urine. Within the next few years, several workers confirmed that the testes

contained a more powerful androgenic factor than did urine--testosterone.

Three research teams, subsidized by competing pharmaceutical companies, raced to

isolate the hormone and publish their results. On May 27, 1935, Karoly Gyula

David and Ernst Laqueur and their colleagues, funded by the Organon company in

Oss, the Netherlands (where Laqueur had long been the scientific adviser),

submitted a now classic paper entitled "On Crystalline Male Hormone from

Testicles (Testosterone)." On August 24 a German journal received from Butenandt

and G. Hanisch, backed by Schering Corporation in Berlin, a paper describing "a

method for preparing testosterone from cholesterol." And on August 31 the

editors of "Helvetica Chimica Acta" received "On the Artificial Preparation of

the Testicular Hormone Testosterone (Androsten-3-one-17-ol)" from Leopold

Ruzicka and A. Wettstein, announcing a patent application in the name of Ciba.

Butenandt and Ruzicka eventually shared the 1939 Nobel Prize for Chemistry for

this discovery.

The struggle for the synthetic testosterone market had begun. By 1937 clinical

trials in humans were already under way, employing injections of testosterone

propionate, a slow-release derivative of testosterone, as well as oral doses of

methyl testosterone, which is broken down in the body more slowly than is

testosterone. These experiments were initially as haphazard and unregulated as

the more primitive methods involving testicular extracts or transplants. In its

early phase, however, synthetic testosterone therapy was reserved primarily for

treating men with hypogonadism, allowing them to develop fully or maintain

secondary sexual characteristics, and for those suffering from a poorly defined

"male climacteric" that included impotence.

Books and Courses

|

Great Websites

|

Excellent Stores

|

Recipe Cook Books

|

|